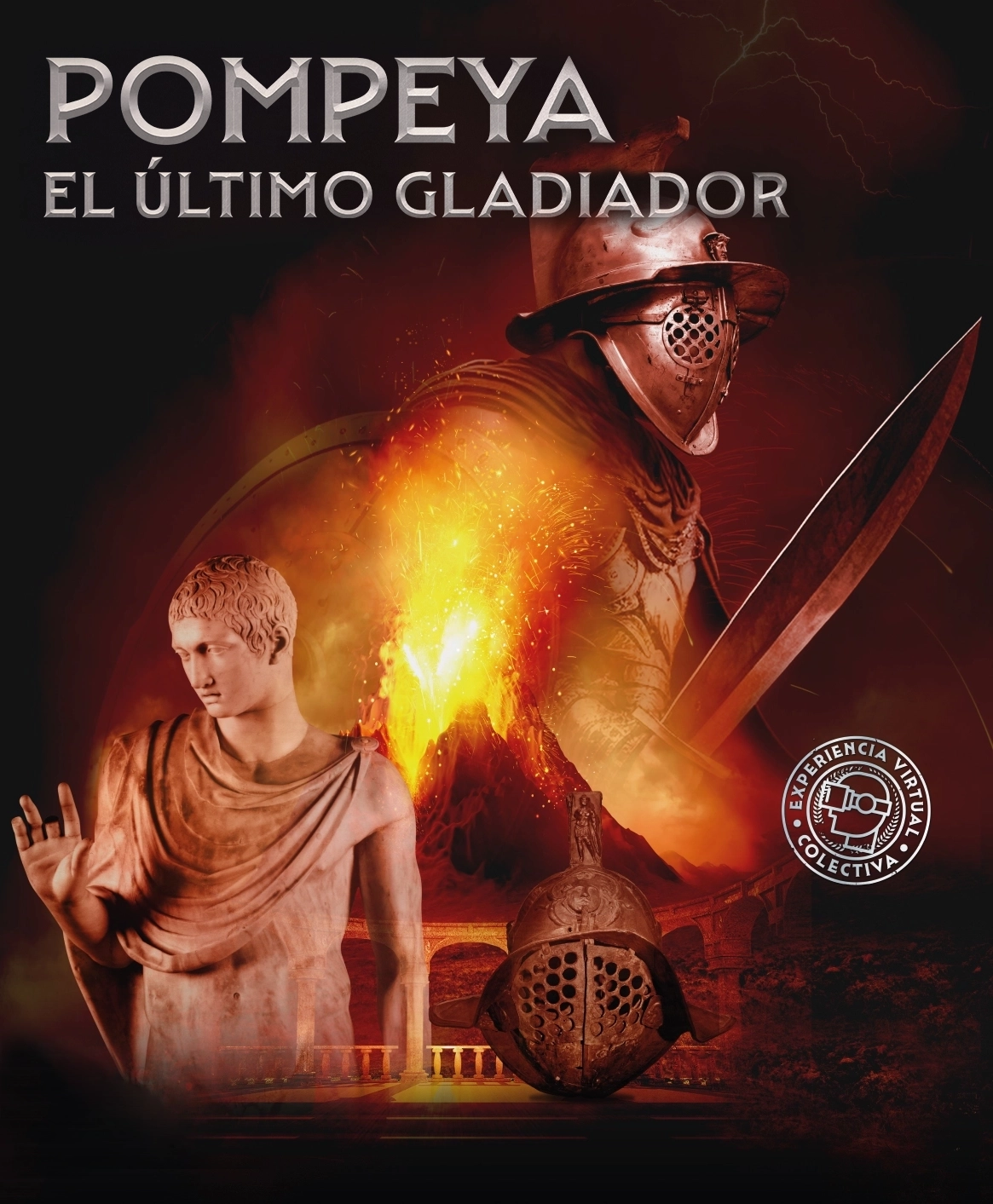

POMPEYA EL ÚLTIMO GLADIADOR

Pompeya, el último gladiador, is a unique and unrepeatable opportunity to immerse oneself in the Pompeii of two thousand years ago, left intact under a blanket of volcanic ash and unveiled in one of the most important and visited archaeological sites in the world.

More than one hundred artifacts from the Museo Mann (National Archaeological Museum of Naples) the archaeological site’s most important landmark museum, allow visitors to enter the heart of daily life in the city buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, A refined narrative, multimedia exhibits produced with the most advanced technology, and a large section dedicated to virtual reality, will offer a highly immersive experience, a multisensory journey of the highest visual impact along the streets of the past, with the suggestions and memory of a civilization fundamental to the development of human progress.

GUERNICA MASTERPIECE GENESYS

What is Guernica?

Guernica is the name of the Basque town that was bombed on the 26th of April 1937 by the German and Italian Condor Legion air force, in support of dictator Francisco Franco. Hundreds of people died in the attack, all civilians. Picasso learned about the news from international newspapers and decided that Guernica would become the theme of his entry to the 1937 Paris Universal Exhibition.

He began working on the monumental artwork only five days after the bombing, and ultimately created a manifesto denouncing the absurd atrocity of war.

The preparatory studies

It took Picasso about 40 days to create Guernica. He made dozens of sketches and preparatory studies to define the composition, the characters, the lights, the colors. He changed his mind multiple times and – since he dated all the drawings – we can clearly follow all the phases of his creative process.

The 42 works displayed in the exhibition are part of an edition made in 1990 by UNESCO and the European Council, with the authorization of the Picasso Foundation.